The current environmental assessment certificate for the PRGT line is set to expire on Nov. 25, 2024

The Prince Rupert Gas Transmission (PRGT) pipeline’s environmental assessment is a point of contention between the Gitanyow First Nation and the Western LNG-Nisga’a First Nation partnership.

The project that was assessed and approved is not the project being currently constructed in the Nass Valley of Terrace, according to Gitanyow.

“As far as we’re concerned, this pipeline needs a new environmental assessment,” said Gamlakyeltxw (Wil Marsden), a chief of the Ganeda Clan.

In August, Marsden shared that Gitanyow is planning to conduct an independent environmental assessment. That assessment is now “fairly close” to being finalized.

“I expect it to be completed within this year,” said Marsden.

The pipeline’s environmental certificate was issued in 2014 when the line was set to connect to a Petronas LNG export facility near Prince Rupert. That project was cancelled in 2017. In 2019, TC Energy applied for and received a five-year extension to the certificate, which expires in November unless the Nisga’a-Western LNG partnership can demonstrate the project has been “substantially started.”

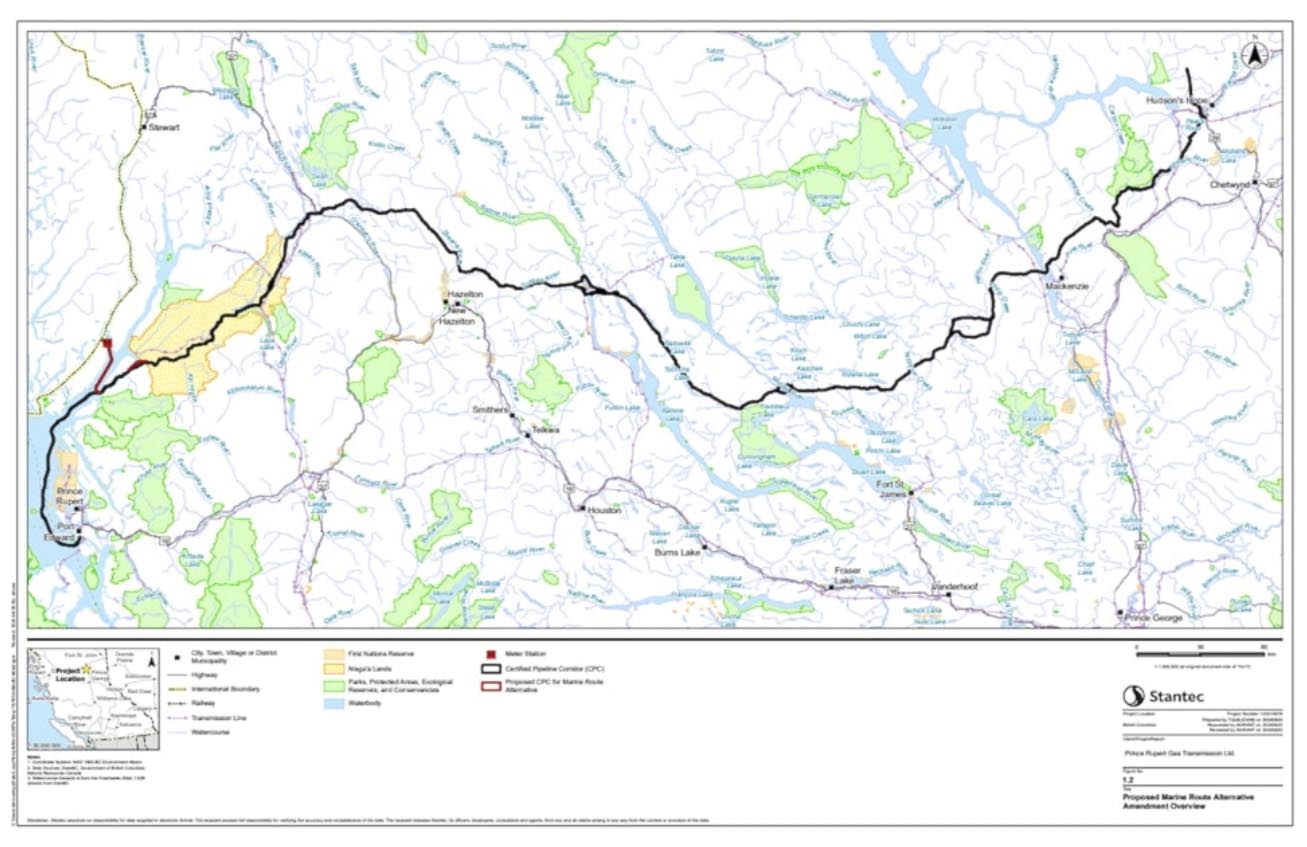

The PRGT line was originally supposed to stretch across northern B.C., turn south at Nass Bay and continue to Port Edward to the proposed Petronas facility. Now, the line would travel north at the Gasoga Gulf, heading up the Portland Inlet to the north end of Pearse Island to supply the proposed Ksi Lisims liquefaction facility near the Nisga’a village of Gingolx.

The Skeena Watershed Coalition created an interactive map illustrating the PRGT pipeline impacts, which can be accessed on their website.

Rebecca Scott, Western LNG’s spokesperson, said they expect an amendment to the current environmental assessment to be approved by the end of the year.

The Nisga’a Nation did not respond to requests for comment.

Naxginkw (Tara Marsden), a Gitanyow member who works with the hereditary chiefs, questioned at an Aug. 19 “Pipeline Impact Meeting” whether Gitanyow was given all the information they needed to make an informed decision 10 years ago when they signed a benefits agreement with the former owner TC Energy.

The difference today, she said, comes down to two factors. The Gitanyow have since implemented fish and wildlife programs that have helped them understand how the habitat will be affected by these projects.

Youth were also not involved in the decision to sign the previous agreement.

“The youth and future generations were left out of [the pipeline] conversation, and I’m scared for my future,” said Drew Harris, a youth organizer for the Skeena Watershed Conservation Coalition.

“I just want you to remember we don’t own the land, the land owns us. If we continue to contaminate our waters, pollute our air and deplete our food sources, where does that leave us?”

Gamlakyeltxw recalled that in 2014, he was told by government and PRGT representatives that the pipeline project would go ahead with or without the permission of Gitanyow. Now, he believes the impacts of climate change are too much to ignore.

“All of our our beaver ponds now are just grasslands, they’re all dried up,” Gamlakyeltxw said. “A lot of our local rivers are the lowest levels we’ve ever been. It’s really bad luck to disrespect Mother Earth, and we’re here to protect her.”

The larger Gitxsan Nation — which Gitanyow is part of — has a track record of independently assessing major projects and their impacts.

The proposed Kemess North Mine project of the mid-2000s was opposed by both the Tse Keh Nay and the Gitxsan House of Nii Kyap. It was located northeast of the foot of Thutade Lake, at the head of the Finlay River, in the Omineca Mountains of B.C.’s northern interior.

Its independent review included a three-person panel consisting of representatives for the federal and provincial governments, and other affected First Nations.

The panel developed a concise set of five sustainability criteria that would help assess the project.

“1. Environmental Stewardship: Is the environment adequately protected through all phases of development, construction, and operation, as well as through the legacy post-closure phase?”

“2. Economic Benefits and Costs: Does the project provide net economic benefits to the people of British Columbia and Canada?”

“3. Social and Cultural Benefits and Costs: Does the Project contribute to community and social well-being of all potentially affected people? Is it compatible with their cultural interests and aspirations?”

“4. Fair Distribution of Benefits and Costs: Are the benefits and costs of development fairly distributed among potentially affected people and interests?”

“5. Present versus Future Generations: Does the Project succeed in providing economic and social benefits now without compromising the ability of future generations to benefit from the environment and natural resources in the mine site area?”

The mine was rejected in 2008 based on this criteria. But this was a one-off case as no shift in policy or practice occurred in the federal or provincial environmental assessment process.

More details on the Gitanyow’s independent review of the PRGT project are not available at the moment.

Read the original article by Harvin Bhathal at Terrace Standard.